Using Claude Code for EHR Informatics: Getting Started, Part I

I’ve been using Claude Code to create cohorts, diagnose bugs, and really accelerate my research workflows. Before getting into the fun stuff though, I want to share how I set up my environment. If you’re new to Claude Code or curious about what goes into my CLAUDE.md files, this post is for you.

Coming up in this series:

- Part II: Skills, plugins, and MCP servers

- Part III: Building a cohort in All of Us with Claude Code

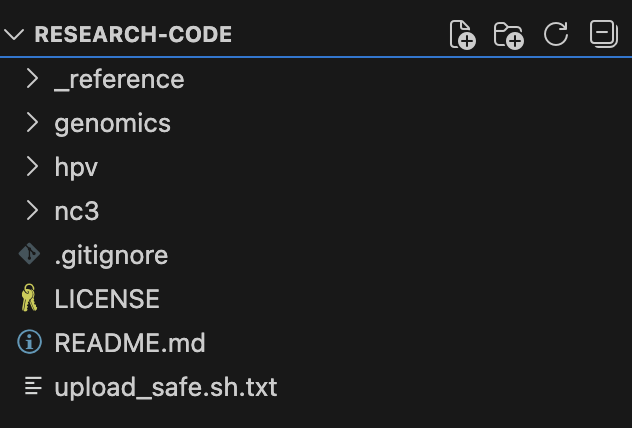

If you’d like to follow along, the GitHub repo is research-code. All files referenced here are available for you to use.

Why Context Matters

But Bennett, can’t I just give Claude a snippet of code and ask it to do something? Sometimes that works well, but the key is context.

If LLM context windows are big enough to consider an entire notebook or project, why limit them? Don’t hide how you derived a cohort when that derivation can inform what you’re asking the model to do next.

At the same time, how do you provide information efficiently without bloating the context window? The .ipynb format includes structural metadata that wastes tokens. References to irrelevant methods add noise without value, and you don’t want to hit your usage limit prematurely.

Claude Code already enables users to review an entire codebase and offer bug fixes or deep understanding. Why not do the same for research? Here’s how I approach it.

1. Centralize Reference Information

The models have been trained on what the internet knows about All of Us, which is both good and bad. They have a general sense of what’s available in the biobank, but for rapidly evolving systems, that information may already be outdated.

For my work, I asked Claude what would be helpful to know. Publicly available data dictionaries exist online, but what details matter most? I downloaded the data dictionary and pared it down to essentials: Table Name, Field Name, OMOP CDM Standard or Custom Field, Description, and Field Type. Claude then generated SQL to provide counts for each table in the current CDR. The result: 9 .tsv files of schema structure and data counts, adhering to the <20 censoring required by All of Us (_reference/all_of_us_tables/).

2. Centralize Phecode Lists

Phecodes are manually curated groupings of ICD codes designed to capture clinically meaningful concepts for research. Lisa Bastarache has an excellent review if you want to learn more. Not every phecode is perfect, but if clinicians and researchers have already worked to group billing codes into meaningful categories, why not start there? We all know about the reproducibility crisis in biomedical research, and random unvalidated ICD groupings aren’t going to help.

This is why I include CSV files mapping phecodes to ICD codes (_reference/phecode/).

3. Identify Trusted Queries

I also brought in a trusted ICD query from my labmate, Tam Tran. He’s the force behind PheTK, a fast Python library for Phenome Wide Association Studies (PheWAS) that includes Cox regression for incident analyses, dsub integration for distributed computing, and more.

In developing PheTK, Tam discovered some peculiarities worth noting:

V-code ambiguity: While most ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes differ structurally, V codes exist in both. V01-V09 means “Persons With Potential Health Hazards Related To Communicable Diseases” in ICD-9-CM but “Pedestrian injured in transport accident” in ICD-10-CM. His query always joins the concept table and matches vocabulary_id.

Dual identifiers: ICD codes appear as both concept_id and concept_code (e.g., 1567285 and A40 for Streptococcal sepsis), and not always both present. His query checks for both.

By keeping these queries in _reference/trusted_queries/, I carry forward these lessons in my code.

4. Collect Your Code

Finally, the important part—your actual code. I work in All of Us, a cloud-based environment where researchers cannot download individual data. To export notebooks safely, I created upload_safe.sh, a script that syncs with my GitHub repo, copies selected notebooks, and strips them of output, bucket paths, and secrets. This way, Claude only sees code—not data.

This was critical for me. In Claude Code, it’s easy to share something unintentionally. I never want to share data I don’t have permission to share.

In this public repo, I’ve included a few published projects:

- genomics: Genomic analysis pipelines for All of Us genetic data

- hpv: HPV research cohorts using OMOP CDR data

- nc3: N3C RECOVER Long COVID phenotyping algorithm adapted for All of Us

Orienting Claude Code

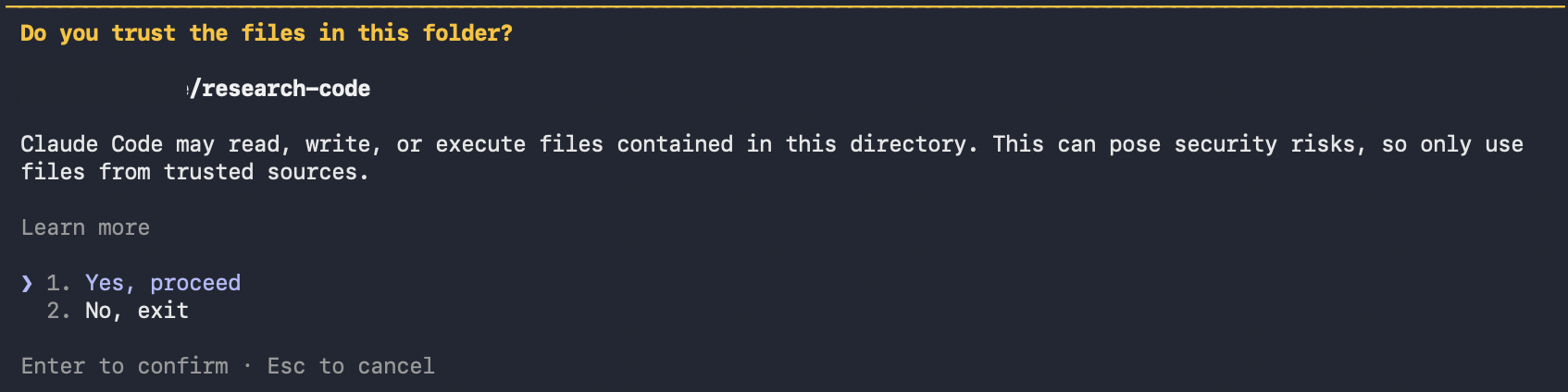

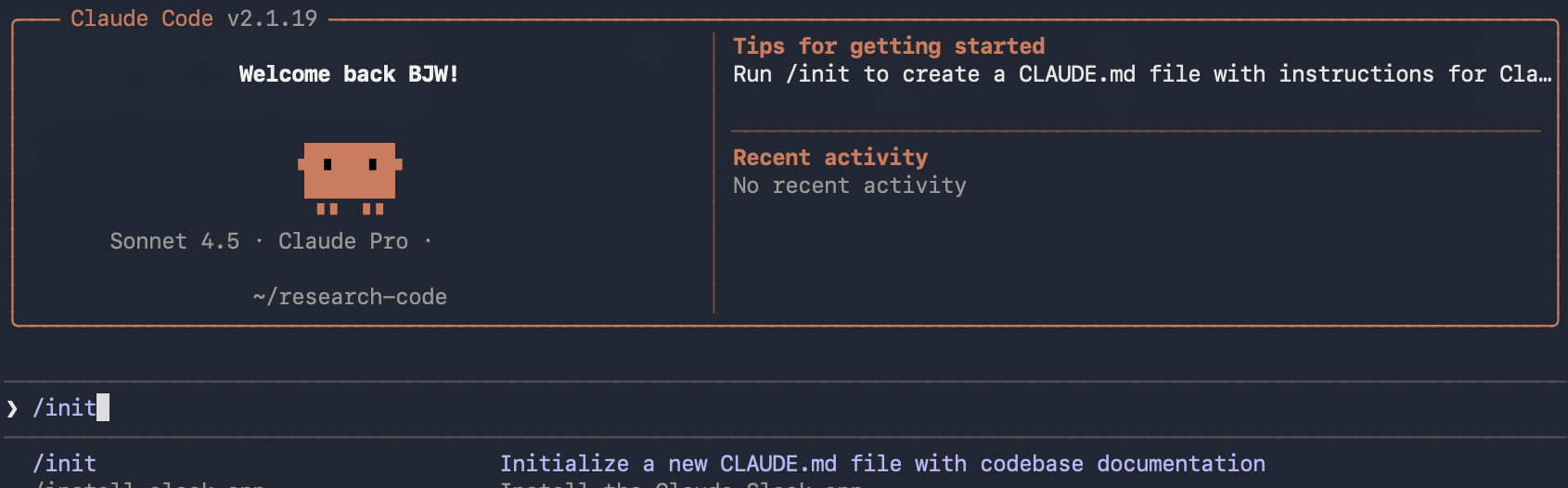

Once all files are in place, you’re ready to initialize. Open terminal, navigate to your working folder, and type claude.

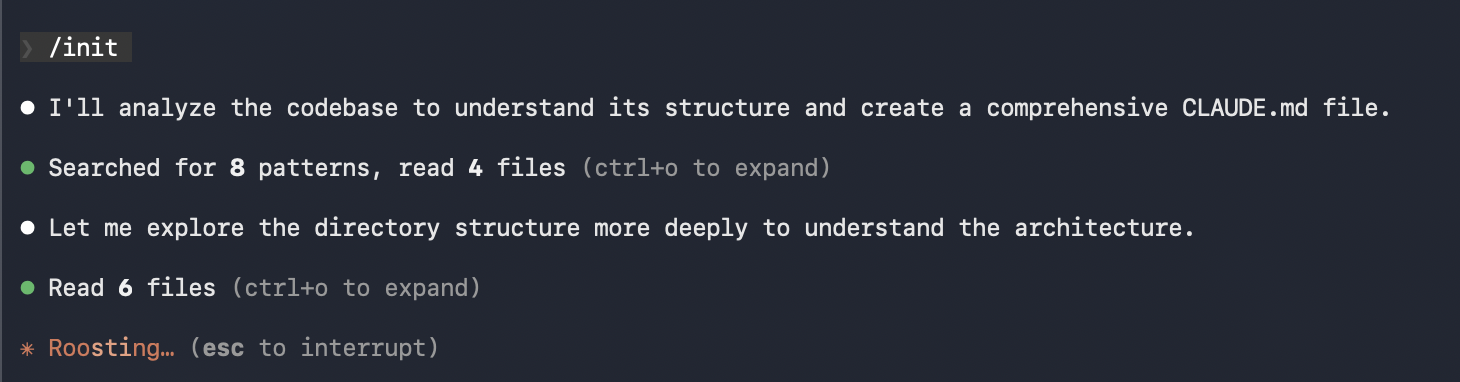

Type /init to create a CLAUDE.md file for the repository root.

CLAUDE.md files define coding standards, review criteria, user preferences, and project-specific rules. Each time you start Claude Code, this document loads into context and guides your session. Anthropic recommends keeping it focused and concise, updating as the repository evolves.

Claude does the heavy lifting. It produces a solid first draft:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

This repository contains computational methods for research informatics

and genomics research, primarily focused on analyzing data from the NIH's

**_All of Us_ Research Program**. Code examples are shared from

bennettwaxse.com and include analysis tools for:

- **Genomics**: Variant analysis, ancestry inference, PCA workflows using PLINK2 and Hail

- **HPV Research**: Cohort construction and analysis

- **N3C/RECOVER**: Long COVID phenotyping algorithms adapted from PySpark to Python/pandas

- **Reference Materials**: _All of Us_ table schemas, PheCode mappings, and Verily Workbench helpers

It included other useful sections: Platform, Key Environment Variables, Code Structure, Project Organization, Data Handling, Common Libraries, and Workflow Patterns.

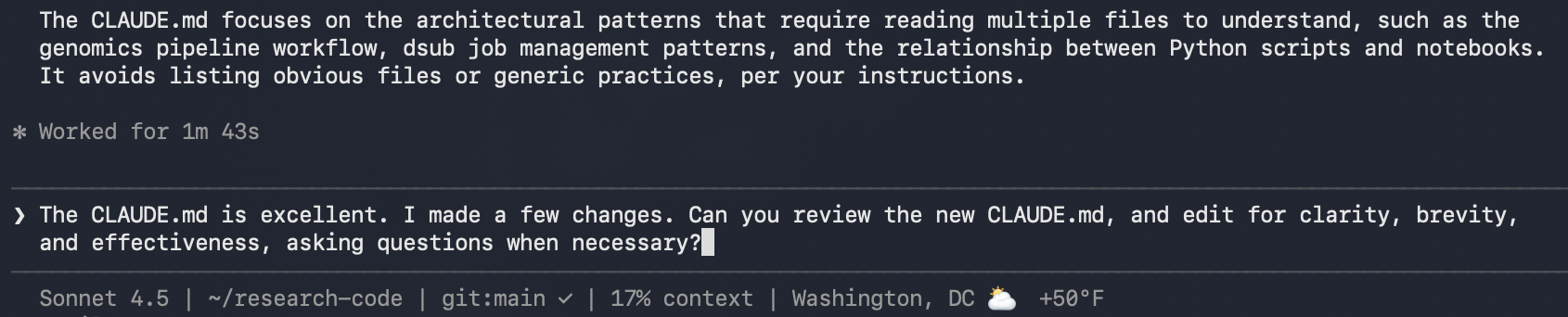

Editing CLAUDE.md

The first draft captured the general intent, but I edited line by line. I added a Development Philosophy section describing the importance of:

- Data validation throughout processing: Check frequently that data transforms as expected

- Code clarity over abstraction: These scripts serve a dual purpose—analysis and teaching EHR/genomics informatics. I want trainees to see exactly how processes work.

I also added a section about All of Us rules, including count censoring for all values <20 to minimize problematic reporting.

Some things Claude got wrong. One section referenced code for setting environment variables in the new Verily Workbench. Claude assumed this was required for every project, so I clarified it’s only for new Verily Workbench notebooks, a work-in-progress for All of Us.

As with everything AI-generated, my mantra: review it line by line. Then iterate. Claude refined my verbose writing and kept things focused.

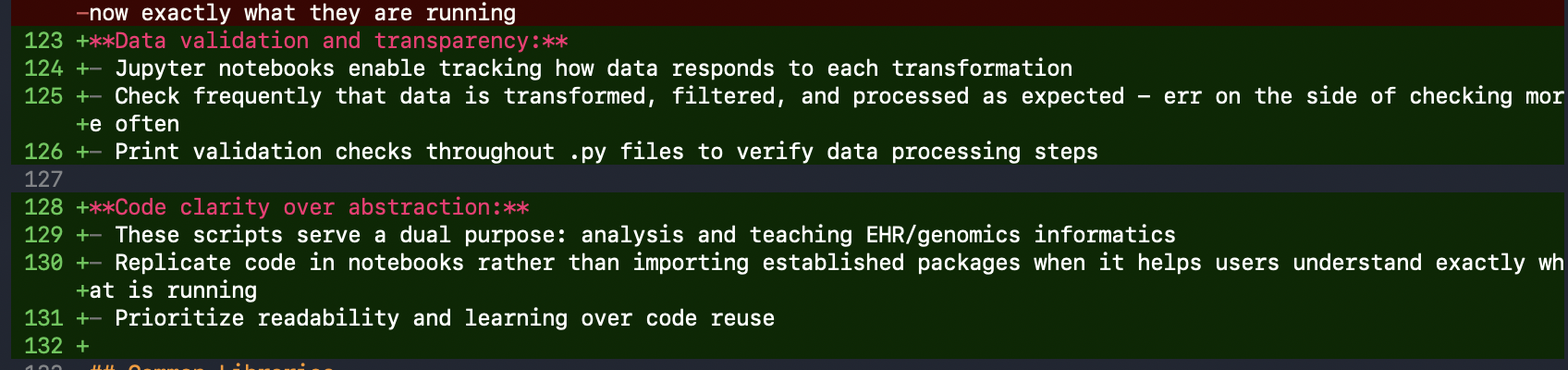

Creating .claudeignore

Next, I asked Claude to create subdirectory CLAUDE.md files. These only load when Claude works in those directories—a good way to reveal specifics only when relevant. Remember, it’s all about efficient context usage.

I created a .claudeignore file to:

- Prevent reading

.ipynbfiles (redundant with.pyscripts) - Block files containing secrets like

.env - Exclude raw data files (

.bam,.fastq)—Claude isn’t analyzing actual data - Skip Python cache, build artifacts, and IDE files

I did keep .csv and .tsv off this list since I share mappings and references with Claude.

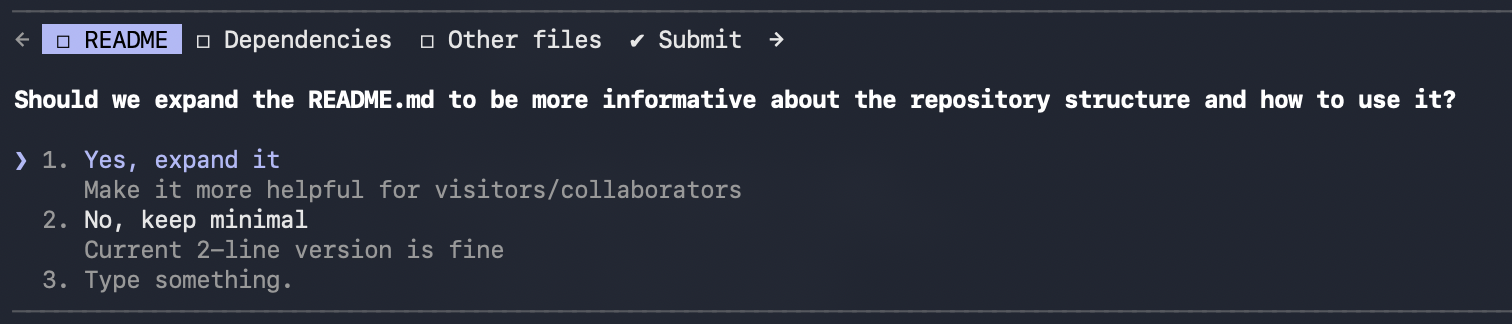

Claude also asked clarifying questions. It offered to expand the README and suggested a few other improvements.

The Result

What we have is a meaningfully structured folder with source material that mirrors my typical workflows and resources. CLAUDE.md files orient Claude to the project, and .claudeignore tells it what to avoid.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

research-code/

├── CLAUDE.md # Root instructions

├── .claudeignore # Files to skip

├── _reference/

│ ├── CLAUDE.md # Reference-specific context

│ ├── all_of_us_tables/ # CDR schemas

│ ├── phecode/ # Phecode mappings

│ └── trusted_queries/ # Vetted SQL patterns

├── genomics/

│ ├── CLAUDE.md # Genomics-specific context

│ └── *.py # Analysis scripts

├── hpv/

│ └── ...

└── nc3/

└── ...

What’s Next

If you’re excited to see what Claude can do with this foundation, you’re in the right place. Next time, I’ll introduce skills, plugins, and MCP servers—components that extend what Claude Code can do!

Soon, you’ll see how Claude Code is supercharging my data analysis in All of Us. If you’re already using Claude Code, I’d love to learn how you’re using it too!

Until then, sciencespeed.

Comments